Morley’s Trisector Theorem states that for any triangle, the three points of intersection of the adjacent angle trisectors form an equilateral triangle. Its beauty lies in the surprising emergence of a perfectly regular shape from an arbitrary starting triangle

Let’s first look at direct proof by trigonometric computations.

For a with angles

, we have the relation

. Let the circumradius of

be

. The side length

.

In , the Law of Sines gives the length of segment

Using the identity , this simplifies to:

By symmetry, for segment in

:

In , we apply the Law of Cosines to find the side length

:

Substituting and factoring yields:

The expression in brackets corresponds to the Law of Cosines for a triangle with angles , and is equal to

. Substituting this back:

Thus, the side length is:

This expression is symmetric in . Therefore,

, and the Morley triangle is equilateral.

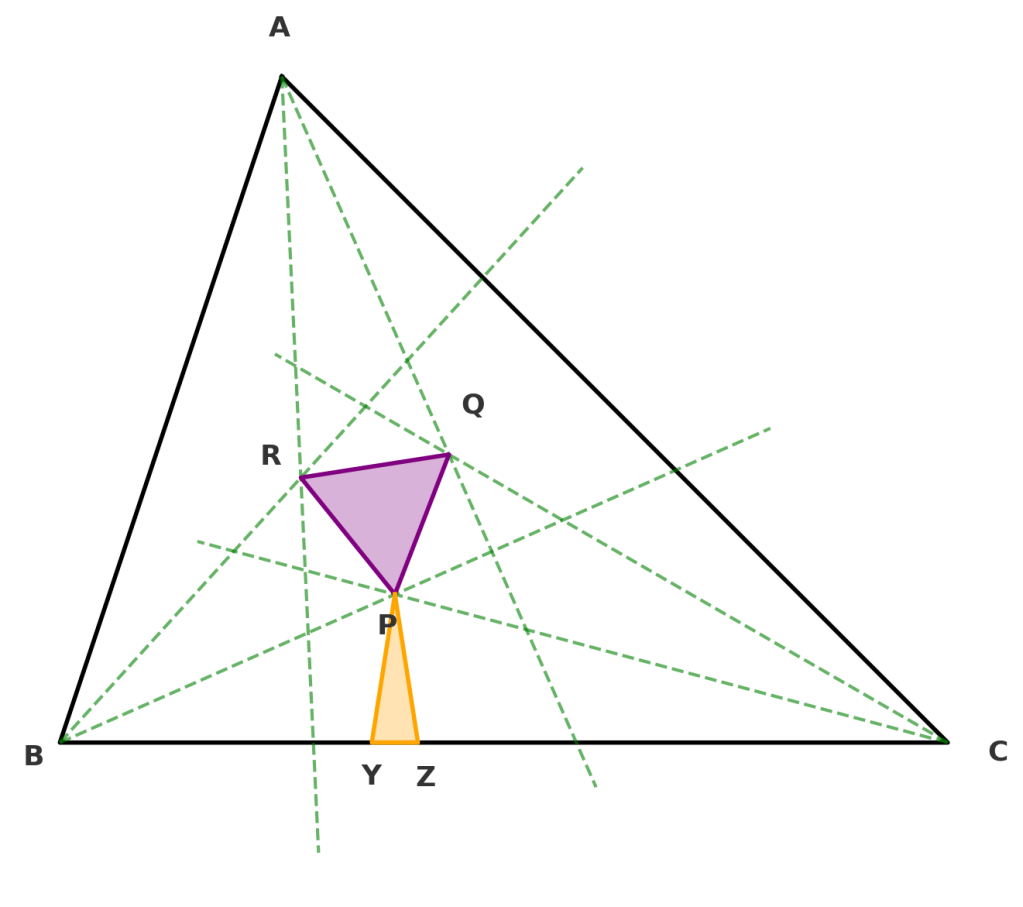

Conway’s Proof

Next we look at a famous proof by John Conway. Conway’s proof is elegant and clever. The proof is a masterpiece of constructive reasoning. Instead of dissecting the original triangle, Conway builds a new figure from seven “abstract” triangular puzzle pieces and shows that it must be similar to the original triangle.

The core idea is to define a set of seven triangles based on the angles of our given triangle. We then show that these seven pieces, when scaled and fitted together, form a perfect replica of the original triangle with its trisectors. Since the central piece of our puzzle is defined to be equilateral, the Morley triangle in the original must also be equilateral.

For a triangle with angles , we have the relation

. The proof uses a set of abstract triangles defined by these angles. The two most important for the argument are:

- The `Outer” Triangle (

): Angles are

,

, and

.

- The `Bridge” Triangle (

): Angles are

,

, and

.

The sizes of the pieces are fixed by setting key lengths to 1.

- The central Morley triangle,

, is equilateral with side length 1, so

.

- The outer triangle

includes an isosceles

with base angles

, scaled so that

.

To prove , we note that they share angle

, have matching angles

, and both have a side of length 1. So by AAS, they are congruent.

This congruence ensures that the side in the bridge triangle matches the one in the outer triangle. By symmetry, this locking holds for all seven abstract pieces, assembling a perfect triangle with angles

.

Since this constructed figure is similar to the original triangle and its central piece () was defined to be equilateral, the Morley triangle of the original triangle must also be equilateral.

Connes’ Proof:

The surprising regularity of the Morley triangle suggests a deep underlying symmetry. To reveal it, we need to change our perspective.

The core idea is to shift our focus from the objects (points and lines) to the transformations that define them. Instead of seeing the Morley vertices as mere intersections of trisector lines, Connes observe that we can view them as invariant points of certain rotations. This shift to the language of transformations and their invariants is where the magic lies.

Let the vertices of the triangle, , be represented by the complex numbers

, and let the angles at these vertices be

, respectively. Define three fundamental rotations about these points:

The central observation is that the Morley triangle vertices—denoted by —are the unique fixed points of the pairwise compositions of these rotations:

This identification turns the geometric puzzle into a question of algebra: do the expressions for satisfy the condition for forming an equilateral triangle?

One approach is to compute everything directly. While effective in proving the result, it obscures the underlying reason the result holds.

First, we derive the explicit (and complex) formulas for in terms of

and the angles. Then, we note the target condition: for the triangle to be equilateral, the equation (as complex numbers)

must hold, where is a primitive cube root of unity. Finally, we substitute the formulas into this equation. Thanks to the angle constraint

and the identity

, the expression simplifies to zero.

This approach conclusively shows that Morley’s Theorem is true, but offers little insight into why it must be true.

Alain Connes realized that a heavy computation is unnecessary. Instead, one can reach the conclusion by examining the algebraic structure of the rotations themselves.

The key idea is a deep symmetry property among the rotations. If each rotation is applied three times in sequence, the result is the identity transformation. That is,

Why does this hold? Each map like represents a rotation by angle

, so

is a rotation by

. In geometric terms, this is equivalent to two reflections across lines meeting at angle

. Repeating this for all three vertices, every side of the triangle is used twice as a reflection line, effectively canceling out. The net transformation is the identity.

This algebraic symmetry implies a geometric consequence, formalized by Connes’s abstract theorem. The theorem states that this symmetry condition is mathematically equivalent to a geometric configuration: the fixed points of the pairwise compositions must form an equilateral triangle.

To prove this, we consider three affine transformations of the form , and aim to show that the algebraic condition

is equivalent to the geometric condition:

where , and the points

are the fixed points of

, respectively.

The identity condition implies two things: the composite rotational part must be 1, and the translational part must be 0.

First, we examine the rotation. The rotational part of the composite map is the product of the individual rotations:

Setting , the condition becomes

, satisfying the first part of the geometric criterion.

Next, we examine the translational part. Denoting the total translation as , a lengthy but straightforward calculation shows:

Connes’s insight was to factor this expression. Using the explicit formulas for the fixed points:

we can rewrite as:

The pre-factor is nonzero under the assumption that none of the compositions degenerate into pure translations. Therefore, the translational part vanishes only when:

This is precisely the condition for to be the vertices of an equilateral triangle. Thus, the algebraic condition implies and is implied by the geometric one. This completes the proof of the abstract theorem.

Since the Morley rotations satisfy the symmetry condition

, it follows inevitably from the theorem that the triangle formed by the fixed points

is equilateral. Connes’s proof reveals that this remarkable geometric result is a natural consequence of a deeper algebraic structure of the affine transformations.