The Law of Quadratic Reciprocity is a cornerstone of classical number theory—Gauss himself called it the “Theorema Aureum” (Golden Theorem). Although Gauss provided multiple proofs, Eisenstein’s geometric argument simplifies Gauss’s third proof by employing a lattice‐point counting method.

Statement of the Law of Quadratic Reciprocity

Let and

be distinct odd primes. The Law of Quadratic Reciprocity (QRL) asserts that

We will recall the definition of the Legendre symbol and Euler’s Criterion, then introduce the key sums that Eisenstein uses, and finally carry out the lattice‐point counting argument.

The Legendre Symbol and Euler’s Criterion

For an odd prime and an integer

, the Legendre symbol

is defined by

Euler’s Criterion gives a practical way to compute when

.

Criterion 1 (Euler’s Criterion). Let be an odd prime and let

be an integer with

. Then

Since both sides are , this congruence implies actual equality.

Eisenstein’s Key Sums

Throughout this section, set . We will introduce two sums:

- The Eisenstein sum

, which runs over even integers in

.

- The geometric sum

, which counts lattice points under a certain line.

Eisenstein’s Sum

Define

Observe that the even integers range over

. For each such

, the quantity

counts the number of integer points with

. Hence,

In other words, counts all integer lattice points

satisfying

The Geometric Sum

Define

Here the summation index runs over all positive integers

. For each

,

counts the integer points with

. Hence,

Geometrically, these are exactly the lattice points strictly below the line

in the interior of the (half‐height) triangle with vertices

In the sequel, we will see that is more convenient than

when performing the final lattice‐point count.

Eisenstein’s Lemma

The first major step is to show that the arithmetic definition of can be expressed in terms of the parity of

.

Lemma 1 (Eisenstein). Let and

be distinct odd primes. Then

Proof Sketch.

- Let

be the set of alleven residues modulo

. For each

, write

Notice thatis some residue in

. Now define

Since, if

is odd then

is even. Hence

runs over exactly the same set

, just permuted.

- Observe the congruence

Equivalently,

Taking the product over allyields

Butis a permutation of

, so

. Since neither product is divisible by

, we cancel

from both sides to obtain

- By Euler’s Criterion,

when

. Thus

- Finally, relate

to

. Since

is even,

is even. Write

Hereis odd or even according to whether

is odd or even, because

itself is odd. But the left‐hand side

is even, so

must have the same parity as

. In symbols:

Therefore,

Combining these congruences shows

completing the proof of the lemma.

Q.E.D.

From  to

to

Eisenstein’s next insight is that, modulo 2, the sum over even (namely

) is congruent to the sum over all

, i.e.

. We give a streamlined parity argument that shows

Relating Even‐ Points to Odd‐

Points to Odd‐ Points

Points

Recall

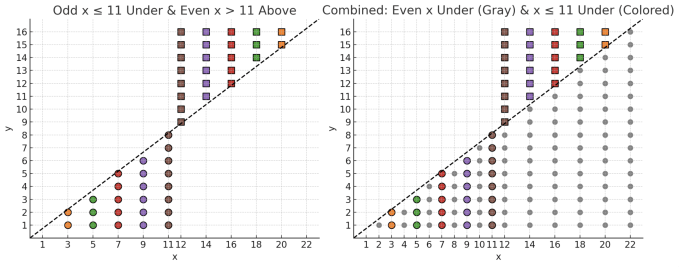

Fix a particular even line . On that vertical line, all integer lattice points have coordinates

with

. Since

is odd,

is even, so there are exactly

points on that vertical line between

and

.

- The number of points strictly below the line

is

- The number of points strictly above

(but with

) is

Since is even, it follows that

We can see that

where is an odd integer in

. Concretely, each point above the line

on the even column

corresponds to a unique point below

on the odd column

. Hence, for each

,

Comparing to

Now break the sum

into two parts: one over odd and one over even

. That is,

Observe that the sum over odd in the range

is exactly

which after reindexing matches

Hence

Since , we conclude

The Main Geometric Counting Argument

We have now re‐expressed

where

We now count all integer points in the rectangle

with . Precisely, we consider

Since there are choices for

and

choices for

, the total number of such lattice points is

No such lattice point lies exactly on the line

because if and

, then

. Since

and

are distinct primes,

, so

must divide

. But

forces

, which is impossible in our index range. Hence all lattice points in

are either strictly below

or strictly above

.

- The points strictly below

(i.e. satisfying

) are counted by

- The points strictly above

(i.e. satisfying

) are counted by

Since these two sets of points partition all lattice points in

, we have

Therefore,

This completes Eisenstein’s geometric proof of the Law of Quadratic Reciprocity.

Concluding Remarks

- The beauty of this argument lies in translating an arithmetic statement about Legendre symbols into a purely geometric enumeration problem.

- Eisenstein’s parity argument shows that summing over even

-coordinates (the original sum

) is congruent mod 2 to summing over all

. This relates the parity of the Eisenstein sum to a sum more geometric.

- The final step is a simple but elegant lattice‐point count in a rectangle, divided by a diagonal line of slope

. No point in the interior can lie exactly on the diagonal, ensuring that every point is counted either “below” or “above.”